Resonant inductive coupling

Resonant inductive coupling or electrodynamic induction is the near field wireless transmission of electrical energy between two coils that are highly resonant at the same frequency. The equipment to do this is sometimes called a resonant or resonance transformer. While many transformers employ resonance, this type has a high Q and is often air cored to avoid 'iron' losses. The two coils may exist as a single piece of equipment or comprise two separate pieces of equipment.

Resonant transfer works by making a coil ring with an oscillating current. This generates an oscillating magnetic field. Because the coil is highly resonant any energy placed in the coil dies away relatively slowly over very many cycles; but if a second coil is brought near it, the coil can pick up most of the energy before it is lost, even if it is some distance away. The fields used are predominately non-radiative, near field (sometimes called evanescent waves), as all hardware is kept well within the 1/4 wavelength distance they radiate little energy from the transmitter to infinity.

One of the applications of the resonant transformer is for the CCFL inverter. Another application of the resonant transformer is to couple between stages of a superheterodyne receiver, where the selectivity of the receiver is provided by tuned transformers in the intermediate-frequency amplifiers.[1] Resonant transformers such as the Tesla coil can generate very high voltages with or without arcing, and are able to provide much higher current than electrostatic high-voltage generation machines such as the Van de Graaff generator.[2] Resonant energy transfer is the operating principle behind proposed short range wireless electricity systems such as WiTricity and systems that have already been deployed, such as passive RFID tags and contactless smart cards.

These types of systems generate magnetic fields that are unlikely to cause health issues in humans.

Contents |

Resonant coupling

Non-resonant coupled inductors, such as typical transformers, work on the principle of a primary coil generating a magnetic field and a secondary coil subtending as much as possible of that field so that the power passing though the secondary is as close as possible to that of the primary. This requirement that the field be covered by the secondary results in very short range and usually requires a magnetic core. Over greater distances the non-resonant induction method is highly inefficient and wastes the vast majority of the energy in resistive losses of the primary coil.

Using resonance can help efficiency dramatically. If resonant coupling is used, each coil is capacitively loaded so as to form a tuned LC circuit. If the primary and secondary coils are resonant at a common frequency, it turns out that significant power may be transmitted between the coils over a range of a few times the coil diameters at reasonable efficiency.[3]

Energy transfer and efficiency

The general principle is that if a given oscillating amount of energy (for example alternating current from a wall outlet) is placed into a primary coil which is capacitively loaded, the coil will 'ring', and form an oscillating magnetic field. The energy will transfer back and forth between the magnetic field in the inductor and the electric field across the capacitor at the resonant frequency. This oscillation will die away at a rate determined by the Q factor, mainly due to resistive and radiative losses. However, provided the secondary coil cuts enough of the field that it absorbs more energy than is lost in each cycle of the primary, then most of the energy can still be transferred.

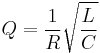

The primary coil forms a series RLC circuit, and the Q factor for such a coil is:

,

,

For R=10 ohm,C=1 micro farad and L=10 mH, Q is given as 1000.

Because the Q factor can be very high, (experimentally around a thousand has been demonstrated[4] with air cored coils) only a small percentage of the field has to be coupled from one coil to the other to achieve high efficiency, even though the field dies quickly with distance from a coil, the primary and secondary can be several diameters apart.

Coupling coefficient

The coupling coefficient is the fraction of the flux of the primary that cuts the secondary coil, and is a function of the geometry of the system. The coupling coefficient is between 0 and 1.

Systems are said to be tightly coupled, loosely coupled, critically coupled or overcoupled. Tight coupling is when the coupling coefficient is around 1 as with conventional iron-core transformers. Overcoupling is when the secondary coil is so close that it tends to collapse the primary's field, and critical coupling is when the transfer in the passband is optimal. Loose coupling is when the coils are distant from each other, so that most of the flux misses the secondary, in Tesla coils around 0.2 is used, and at greater distances, for example for inductive wireless power transmission, it may be lower than 0.01.

Power transfer

Because the Q can be very high, even when low power is fed into the transmitter coil, a relatively intense field builds up over multiple cycles, which increases the power that can be received—at resonance far more power is in the oscillating field than is being fed into the coil, and the receiver coil receives a percentage of that.

Voltage gain

The voltage gain of resonantly coupled coils is proportional to the square root of the ratio of secondary and primary inductances.

Transmitter coils and circuitry

Unlike the multiple-layer secondary of a non-resonant transformer, coils for this purpose are often single layer solenoids (to minimise skin effect and give improved Q) in parallel with a suitable capacitor, or they may be other shapes such as wave-wound litz wire. Insulation is either absent, with spacers, or low permittivity, low loss materials such as silk to minimise dielectric losses.

To progressively feed energy/power into the primary coil with each cycle, different circuits can be used. One circuit employs a Colpitts oscillator.[4]

In Tesla coils an intermittent switching system, a "circuit controller or "break," is used to inject an impulsive signal into the primary coil; the secondary coil then rings and decays.

Receiver coils and circuitry

The secondary receiver coils are similar designs to the primary sending coils. Running the secondary at the same resonant frequency as the primary ensures that the secondary has a low impedance at the transmitter's frequency and that the energy is optimally absorbed.

To remove energy from the secondary coil, different methods can be used, the AC can be used directly or rectified and a regulator circuit can be used to generate DC voltage.

History

In 1894 Nikola Tesla used resonant inductive coupling, also known as "electro-dynamic induction" to wirelessly light up phosphorescent and incandescent lamps at the 35 South Fifth Avenue laboratory, and later at the 46 E. Houston Street laboratory in New York City.[5][6][7] In 1897 he patented a device[8] called the high-voltage, resonance transformer or "Tesla coil." Transferring electrical energy from the primary coil to the secondary coil by resonant induction, a Tesla coil is capable of producing very high voltages at high frequency. The improved design allowed for the safe production and utilization of high-potential electrical currents, "without serious liability of the destruction of the apparatus itself and danger to persons approaching or handling it."

In the early 1960s resonant inductive wireless energy transfer was used successfully in implantable medical devices[9] including such devices as pacemakers and artificial hearts. While the early systems used a resonant receiver coil, later systems[10] implemented resonant transmitter coils as well. These medical devices are designed for high efficiency using low power electronics while efficiently accommodating some misalignment and dynamic twisting of the coils. The separation between the coils in implantable applications is commonly less than 20 cm. Today resonant inductive energy transfer is regularly used for providing electric power in many commercially available medical implantable devices.[11]

Wireless electric energy transfer for experimentally powering electric automobiles and buses is a higher power application (>10 kW) of resonant inductive energy transfer. High power levels are required for rapid recharging and high energy transfer efficiency is required both for operational economy and to avoid negative environmental impact of the system. An experimental electrified roadway test track built circa 1990 achieved 80% energy efficiency while recharging the battery of a prototype bus at a specially equipped bus stop.[12][13] The bus could be outfitted with a retractable receiving coil for greater coil clearance when moving. The gap between the transmit and receive coils was designed to be less than 10 cm when powered. In addition to buses the use of wireless transfer has been investigated for recharging electric automobiles in parking spots and garages as well.

Some of these wireless resonant inductive devices operate at low milliwatt power levels and are battery powered. Others operate at higher kilowatt power levels. Current implantable medical and road electrification device designs achieve more than 75% transfer efficiency at an operating distance between the transmit and receive coils of less than 10 cm.

In 1995, Professor John Boys and Prof Grant Covic, of The University of Auckland in New Zealand, developed systems to transfer large amounts of energy across small air gaps.

In 1998, RFID tags were patented that were powered in this way.[14]

In November 2006, Marin Soljačić and other researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology applied this near field behavior, well known in electromagnetic theory, the wireless power transmission concept based on strongly-coupled resonators.[15][16][17] In a theoretical analysis,[18] they demonstrate that, by designing electromagnetic resonators that suffer minimal loss due to radiation and absorption and have a near field with mid-range extent (namely a few times the resonator size), mid-range efficient wireless energy-transfer is possible. The reason is that, if two such resonant circuits tuned to the same frequency are within a fraction of a wavelength, their near fields (consisting of 'evanescent waves') couple by means of evanescent wave coupling (which is related to quantum tunneling). Oscillating waves develop between the inductors, which can allow the energy to transfer from one object to the other within times much shorter than all loss times, which were designed to be long, and thus with the maximum possible energy-transfer efficiency. Since the resonant wavelength is much larger than the resonators, the field can circumvent extraneous objects in the vicinity and thus this mid-range energy-transfer scheme does not require line-of-sight. By utilizing in particular the magnetic field to achieve the coupling, this method can be safe, since magnetic fields interact weakly with living organisms.

Comparison with other technologies

Compared to inductive transfer in conventional transformers, except when the coils are well within a diameter of each other, the efficiency is somewhat lower (around 80% at short range) whereas tightly coupled conventional transformers may achieve greater efficiency (around 90-95%) and for this reason it cannot be used where high energy transfer is required at greater distances.

However, compared to the costs associated with batteries, particularly non-rechargeable batteries, the costs of the batteries are hundreds of times higher. In situations where a source of power is available nearby, it can be a cheaper solution.[19] In addition, whereas batteries need periodic maintenance and replacement, resonant energy transfer could be used instead. Batteries additionally generate pollution during their construction and their disposal which largely would be avoided.

Regulations and safety

Unlike mains-wired equipment, no direct electrical connection is needed and hence equipment can be sealed to minimize the possibility of electric shock.

Because the coupling is achieved using predominantly magnetic fields; the technology may be relatively safe. Safety standards and guidelines do exist in most countries for electromagnetic field exposures (e.g.[20][21]) Whether the system can meet the guidelines or the less stringent legal requirements depends on the delivered power and range from the transmitter.

Deployed systems already generate magnetic fields, for example induction cookers and contactless smart card readers.

Uses

- Contactless smart card

- High voltage (one million volt) sources for X-ray production[22]

- Tesla coils

See also

- Ubeam[23]

- WiTricity

- Wireless Resonant Energy Link (WREL)

- eCoupled for particular implementations of this technology.

- Inductance

- RFId some passive id tags are powered by radio frequency transmissions

- Microwave power transmission an alternative, much longer range way of transferring energy

- Odd sympathy similar resonances occur with mechanical pendulums

- Evanescent wave coupling essentially the same process at optical frequencies

- Wardenclyffe tower

External links

- IEEE Spectrum: A critical look at wireless power

- Intel: Cutting the Last Cord, Wireless Power

- Yahoo News: Intel cuts electric cords with wireless power system

- BBC News: An end to spaghetti power cables

- Instructables: wireless power

- "Marin Soljačić (researcher team leader) home page on MIT". http://www.mit.edu/%7Esoljacic/wireless_power.html.

- Jonathan Fildes (2007-06-07). "Wireless energy promise powers up". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/6725955.stm.

- JR Minkel (2007-06-07). "Wireless Energy Lights Bulb from Seven Feet Away". Scientific American. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleid=07511C52-E7F2-99DF-3FA6ED2D7DC9AA20&chanId=sa025.

- "Breakthrough to a wireless (electricity) future (WiTricity)". The Press Association. 2007-06-07. http://www.breitbart.com/article.php?id=paWirelessThur19Wirelesspower&show_article=1&catnum=0.

- Katherine Noyes (2007-06-08). "MIT Wizards Zap Electricity Through the Air". TechNewsWorld. http://www.technewsworld.com/story/57757.html.

- Chris Peredun, Kristopher Kubicki (2007-06-11). "MIT Engineers Unveil Wireless Power System". DailyTech. http://www.dailytech.com/MIT+Engineers+Unveil+Wireless+Power+System/article7632.htm.

- "Supporting Online Material for Wireless Power Transfer via Strongly Coupled Magnetic Resonances". Science Magazine. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/data/1143254/DC1/1.

- Gary Peterson (2008-08-06). "Anticipating Witricity". 21st Century Books. http://www.tfcbooks.com/articles/witricity.htm.

- William C. Brown biography on the IEEE MTT-S website

- Anuradha Menon (2008-11-14). "Intel’s Wireless Power Technology Demonstrated". The Future of Things e-magazine. http://thefutureofthings.com/news/5763/intel-s-wireless-power-technology-demonstrated.html.

References

- ^ Carr, Joseph. Secrets of RF Circuit Design. pp. pp. 193–195}. ISBN 0071370676.

- ^ Abdel-Salam, M. et al.. High-Voltage Engineering: Theory and Practice. pp. 523–524. ISBN 0824741528.

- ^ Steinmetz, Dr. Charles Proteus, Elementary Lectures on Electric Discharges, Waves, and Impulses, and Other Transients, 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1914. Books.google.com. 2008-08-29. http://books.google.com/?id=Q_ltAAAAMAAJ&dq=%22Elementary+Lectures+on+Electric+Discharges,+Waves,+and+Impulses%22&printsec=frontcover. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ^ a b Wireless Power Transfer via Strongly Coupled Magnetic Resonances André Kurs, Aristeidis Karalis, Robert Moffatt, J. D. Joannopoulos, Peter Fisher, Marin Soljacic

- ^ "Experiments with Alternating Currents of Very High Frequency and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination, AIEE, Columbia College, N.Y., May 20, 1891". 1891-06-20. http://www.tfcbooks.com/tesla/1891-05-20.htm.

- ^ "Experiments with Alternate Currents of High Potential and High Frequency, IEE Address,' London, February 1892". 1892-02-00. http://www.tfcbooks.com/tesla/1892-02-03.htm.

- ^ "On Light and Other High Frequency Phenomena, 'Franklin Institute,' Philadelphia, February 1893, and National Electric Light Association, St. Louis, March 1893". 1893-03-00. http://www.tfcbooks.com/tesla/1893-02-24.htm.

- ^ U.S. Patent 593,138 Electrical Transformer

- ^ J. C. Schuder, “Powering an artificial heart: Birth of the inductively coupled-radio frequency system in 1960,” Artificial Organs, vol. 26, no. 11, pp. 909–915, 2002.

- ^ SCHWAN M. A. and P.R. Troyk, "High efficiency driver for transcutaneously coupled coils" IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society 11th Annual International Conference, November 1989, pp. 1403-1404.

- ^ "What is a cochlear implant?". Cochlearamericas.com. 2009-01-30. http://www.cochlearamericas.com/Products/11.asp. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ^ Systems Control Technology, Inc, "Roadway Powered Electric Vehicle Project, Track Construction and Testing Program". UC Berkeley Path Program Technical Report: UCB-ITS-PRR-94-07, http://www.path.berkeley.edu/PATH/Publications/PDF/PRR/94/PRR-94-07.pdf

- ^ Shladover, S.E., “PATH at 20: History and Major Milestones”, Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference, 2006. ITSC '06. IEEE 2006, pages 1_22-1_29.

- ^ RFID Coil Design

- ^ "Wireless electricity could power consumer, industrial electronics". MIT News. 2006-11-14. http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2006/wireless.html.

- ^ "Gadget recharging goes wireless". Physics World. 2006-11-14. http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/26422.

- ^ "'Evanescent coupling' could power gadgets wirelessly". NewScientist.com news service. 2006-11-15. http://www.newscientisttech.com/article/dn10575-evanescent-coupling-could-power-gadgets-wirelessly.html.

- ^ Aristeidis Karalis; J.D. Joannopoulos, Marin Soljačić (2008). "Efficient wireless non-radiative mid-range energy transfer". Annals of Physics 323: 34–48. Bibcode 2008AnPhy.323...34K. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2007.04.017. "Published online: April 2007"

- ^ "Eric Giler demos wireless electricity". TED. 2009-07. http://www.ted.com/talks/eric_giler_demos_wireless_electricity.html. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- ^ http://www.icnirp.de/documents/emfgdl.pdf ICNIRP Guidelines Guidelines for Limiting Exposure to Time-Varying ...

- ^ IEEE C95.1

- ^ [1]

- ^ Ubeam